An investigative analysis of the 2025 Madhya Pradesh cough syrup tragedy and the global pattern of toxic contamination in children’s medicines by Mounika Bhukya, CPSP’s Project and Policy Officer.

*Warning: This article discusses suicidal behaviour and accidental poisoning. If you have questions on self-harm or feel suicidal, use this link to find an international helpline.*

Summary

On 9 October 2025, reports from Indian authorities confirmed that a widely used children’s cough syrup linked to multiple deaths in Madhya Pradesh contained dangerously high levels of diethylene glycol (DEG) an industrial solvent that is acutely toxic when ingested (Reuters 2025).

At least 20 children under five died after taking the syrup and the manufacturer’s owner was arrested as police and regulators moved to recall affected stock (Reuters 2025).

This report explains the chemistry and medical harms of DEG traces how contaminated medicines have repeatedly reappeared worldwide and identifies systemic fault lines that allow such tragedies to happen.

The immediate tragedy: what happened in Madhya Pradesh

Between late September and early October 2025 clinicians in Chhindwara Betul and surrounding districts reported clusters of previously healthy children presenting with acute kidney injury and rapid multi‑organ failure.

Laboratory testing by Indian authorities identified very high concentrations of diethylene glycol (DEG) in at least one branded cough syrup and traces in others; state and national drug controllers ordered product recalls and suspended the implicated manufacturer’s operations while criminal probes proceeded (Reuters 2025).

The epidemiologic pattern, clusters of infants progressing rapidly to anuric kidney failure, is the classic clinical signature of DEG poisoning (WHO 2023).

What is diethylene glycol (DEG) and why is it deadly?

Diethylene Glycol(DEG) poisoning presents clinically as “break fluid” ingestion or when DEG is replaced as a cheaper alternative solvent in liquid medications, as occurred in Madya Pradesh (McMartin, Jacobsen et al. 2016).

DEG poisoning presents in three phases: initial gastrointestinal symptoms along with metabolic acidosis, a second phase of acute kidney injury developing after one to three days in which death can occur unless treated, and a final stage of neurological features after five to seven days, causing facial palsy, peripheral neuropathy leading to paralysis, and may be fatal (Schep, Slaughter et al. 2009).

Accumulation of metabolites of DEG causes toxicity, with five HEAA leading to acidosis and glycolic acid, which is nephrotoxic.

Therefore, preventing the formation of these metabolites is the cornerstone of treatment.

There is evidence from animal studies and clinical evidence based on case reports that Fomepizole prevents toxic metabolite formation from DEG, but Fomepezole is not an FDA-approved drug for the treatment of DEG poisoning (Rollins, Filley et al. 2002).

Crucially DEG and crude or contaminated glycerin can be visually similar which creates risk when supply‑chain controls or testing are inadequate or bypassed (WHO 2023).

When ingested DEG is metabolised into toxic acids that damage the kidneys and nervous system.

In infants and young children even small exposures frequently produce severe acute kidney injury (AKI) metabolic acidosis and multi‑organ failure.

Clinical series and toxicology reviews document high case‑fatality rates when dialysis and intensive care are not immediately available (Perazella 2023).

This is not new: a recurring global failure

The Madhya Pradesh deaths sit in a long preventable lineage of medicine‑contamination disasters.

The seminal modern example is the 1937 Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster in the United States a DEG‑contaminated preparation that killed more than a hundred people and catalysed the 1938 Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDA 1938).

Since then DEG contamination of medicines has recurred repeatedly across regions and decades.

Most recently a multi‑country wave in 2022–2023 involved numerous contaminated syrup products and was linked to more than 300 reported paediatric fatalities across several low‑ and middle‑income countries; WHO alerts and clinical reports documented clusters in countries including Gambia, Uzbekistan and Indonesia (WHO 2023; Chemistry World 2023).

Where the fault lines are

Multiple overlapping system failures allow a toxic industrial solvent to reach children’s mouths in labelled medicines.

The most important are:

1. Adulteration or contamination of high‑risk excipients (notably glycerin): glycerin is widely used in syrups; if suppliers provide contaminated or substituted material the final product can be lethal without batch‑level verification (WHO 2023).

2. Inadequate raw‑material and finished‑product testing: some manufacturers rely on suppliers’ certificates rather than independent testing or operate laboratories with inadequate methods or oversight; regulators with limited capacity cannot test every incoming batch.

3. Regulatory gaps and enforcement shortfalls: laws may exist on paper but enforcement of inspections, rapid lab testing and traceability is underfunded in many regions.

4. Informal distribution channels: when medicines flow through unregulated retailers, recalls and contact tracing becomes extraordinarily difficult.

5. Commercial incentives to cut costs: cheaper non‑pharmaceutical inputs and lax quality systems can save producers money in the short term, with catastrophic consequences for consumers.

Together these fault lines mean a contaminated batch, even from a single bad‑actor firm or supplier, can create large local crisis and cross borders through informal exports (WHO 2023).

Linking to broader chemical safety and governance failures

The Madya Pradish tragedy is not an isolated pharmaceutical failure but a symptom of a deeper systemic problem.

The current regulatory systems in India are unable to monitor the close access and availability of hazardous substances in the market.

This kind of weak regulation in the pharma industry mirrors similar deficiencies in other domains of chemical control, including certain highly hazardous pesticides (HHPs) and industrial- chemicals, where lethal products are still marketed in the name of agricultural productivity and economic growth.

The Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention[1] (CPSP) has documented how these parallel systems of weak oversight and fragmented accountability expose millions to avoidable harm (Eddleston and Gunnell 2020).

Across rural and peri-urban settings in India, communities live amid unregulated or mislabeled products that contain lethal compounds, from toxic cough syrups to unsafe pesticides, hazards that regulators often assume will not reach end-users or will be used “safely”, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

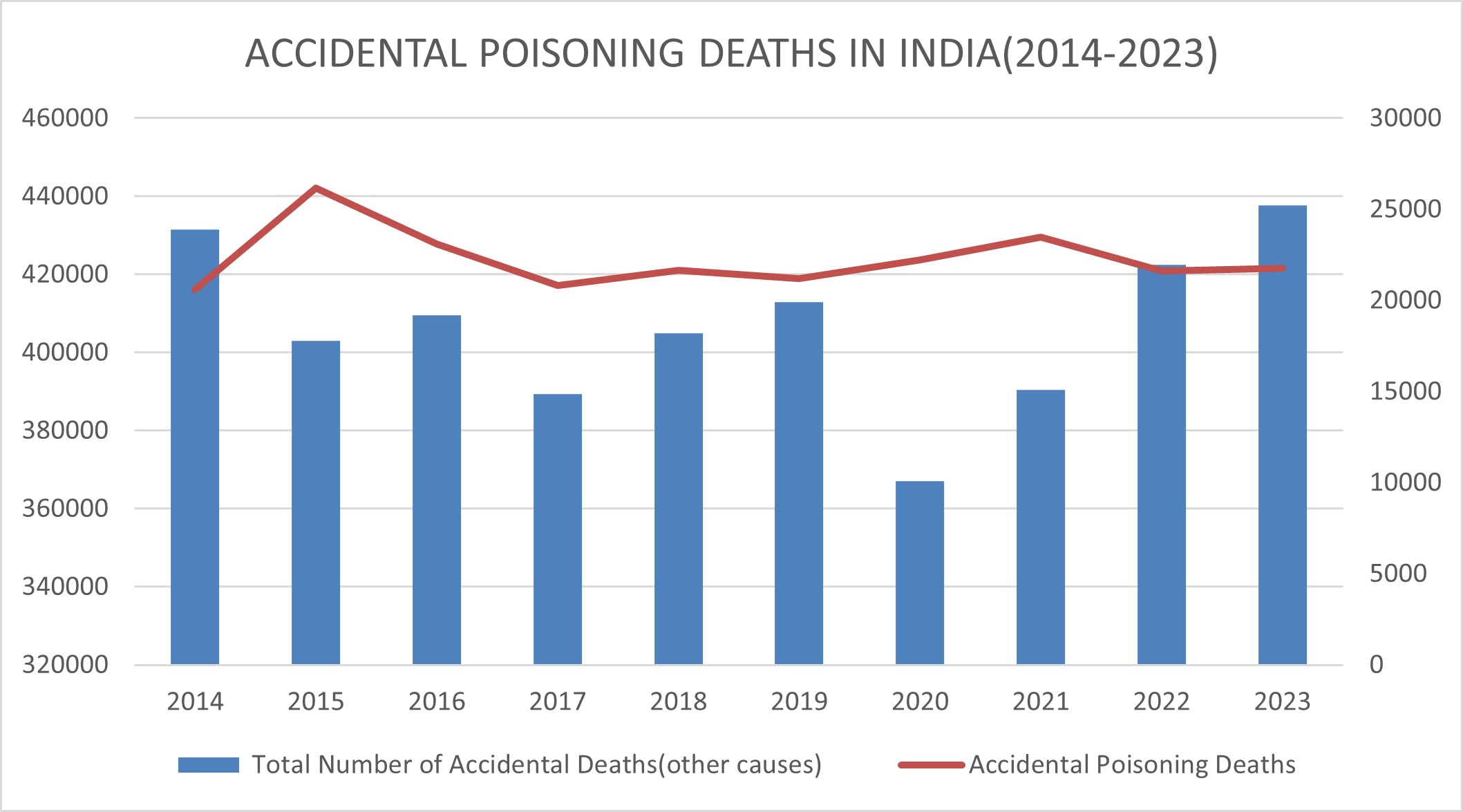

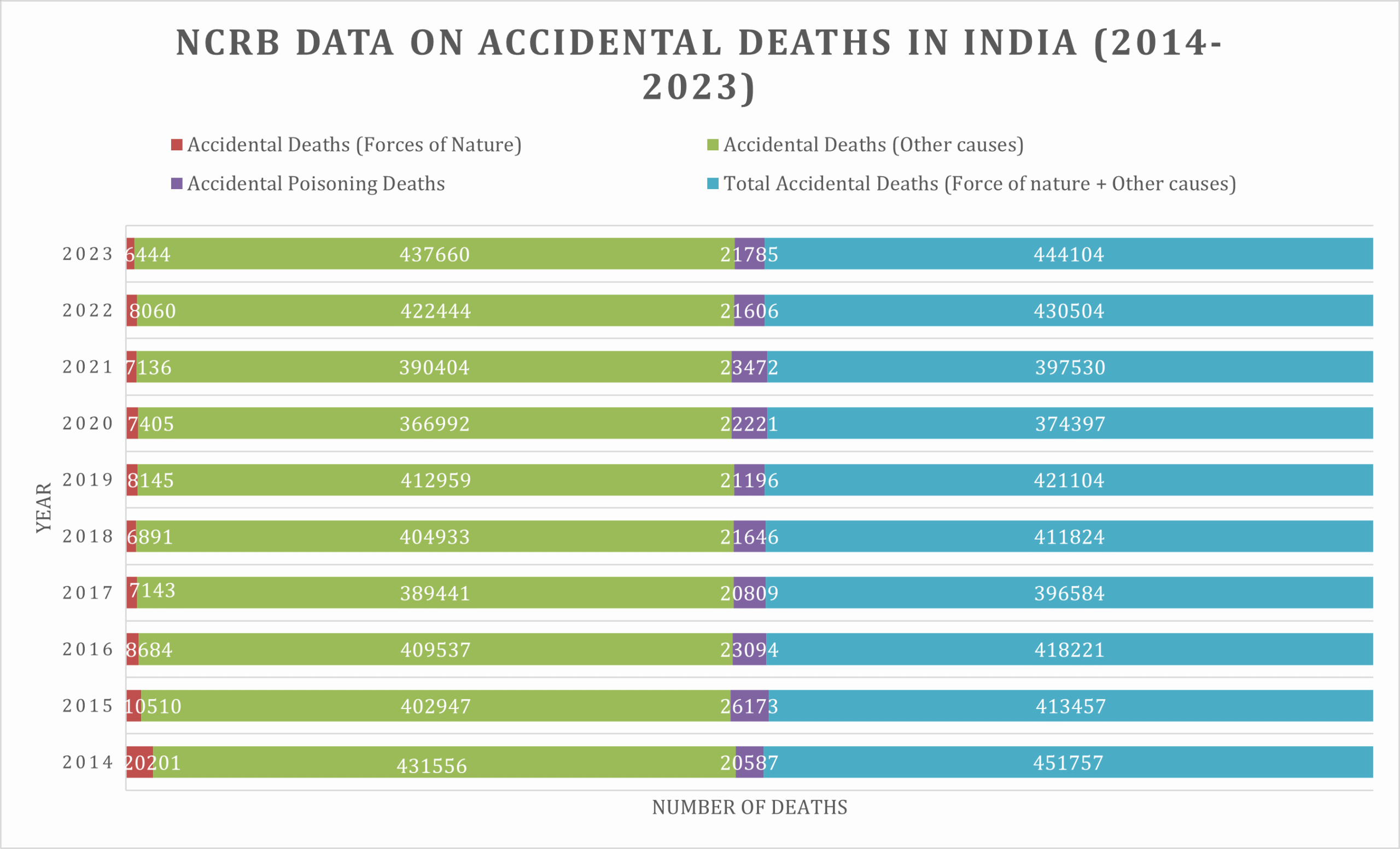

According to the National Crime Record Bureau, Government of India, India sees four lakh accidental deaths annually.

These deaths are segregated into deaths due to “forces of nature” and deaths due to “other causes” (Appendix 1).

It is generally accepted that accidents due to ‘Other Causes’ are preventive and can be reduced by effective safety measures and safety consciousness.

A total of 7,30,821 cases of accidents due to ‘Other Causes’ were reported in the country which resulted in 4,37,660 deaths and 4,53,008 persons injured during 2023 alone (Bureau 2023).

Additionally, a national review synthesizing NCRB data, studies, and regulatory actions reports 441,918 intentional pesticide poisoning incidents (1995–2015) (Bonvoisin, Utyasheva et al. 2020).

The table below shows the contribution of poisoning accidents from 2014-2023. It shows more that two lakh accidental poisoning incidents during this time period[2].

Source: National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of home, ministry of Home affairs, GoI

Accidental and intentional poisoning from highly toxic chemicals is emerging as a severe public health crisis and a man-made catastrophe in India, either through negligence, self-harm or misuse.

The existence of these chemical risks has been normalised overtime, that is, in truth, simply unacceptable.

Strengthening chemical-safety frameworks, from pharmaceuticals to pesticides to industrial-chemicals, therefore requires not only better enforcement but also a shift in the mindset: from a reactive crisis management to proactive, precautionary protection of public health.

How India fits into the global picture

India is a major global manufacturer of generics and active pharmaceutical ingredients, a critical source for medicines worldwide.

That scale is a global public‑health good but it also concentrates risk: a contaminated excipient or an inadequately controlled small manufacturer can have outsized impacts domestically and abroad.

The 2025 Madhya Pradesh outbreak adds to a string of incidents that have raised questions about domestic screening capacity and supply‑chain traceability prompting renewed scrutiny from international bodies (Reuters 2025; WHO 2023).

This is not to say India is uniformly negligent.

Many reputable Indian manufacturers produce high‑quality medicines for export and domestic use.

But the ecosystem also includes a large number of small firms whose compliance varies, which is why independent testing, strong regulatory oversight and transparent supply‑chain practices are essential.

Other Notable Outbreaks of Diethylene Glycol (DEG) Poisoning

|

Year / Period |

Location |

Summary |

Source (Author–Date) |

|

1937 |

United States |

Elixir Sulfanilamide: more than 100 deaths; this event underpinned major US regulatory reform. |

FDA (1938) |

|

2008–2009 |

Nigeria |

Clusters of paediatric AKI linked to DEG‑contaminated teething medications and other syrups. |

CDC (2009) |

|

2022 |

Gambia |

Dozens of children presented with AKI after taking contaminated syrups; high case fatality reported. |

WHO (2023) |

|

2025 |

Madhya Pradesh India |

Approximately 20 paediatric deaths reported; cough syrup found to contain very high levels of DEG. |

Reuters (2025) |

What meaningful reform looks like

There are no magic bullets but practical public‑health gains are within reach if policymakers, regulators industry and international organisations act together.

Priority reforms include:

1. Mandatory independent batch testing of high‑risk excipients (glycerin) and finished syrups before products reach the market with results recorded in a central auditable registry (WHO 2023).

2. Harmonised rapid‑response laboratory networks with accredited methods to test for DEG and related contaminants supported by international partners where domestic capacity is limited (WHO 2023).

3. Stronger supplier audits and transparency: mandatory traceability (lot number certificates of analysis supplier registries) and legal penalties for falsified documentation.

4. Tougher enforcement and legal frameworks that make deliberate adulteration a serious criminal offence coupled with commercial penalties for negligent quality systems.

5. Public‑health guidance to clinicians and caregivers advising caution with non‑essential cough syrups in young children and emphasising procurement from verified pharmacies and prescribers.

6. International cooperation: WHO‑led alert systems must be resourced and linked to customs and export monitoring to reduce cross‑border spread of contaminated products.

Accountability not scapegoating

Criminal investigations and prosecutions are necessary where evidence of deliberate wrongdoing exists but they are insufficient if they stop at individual actors.

Structural failures require systemic reform: regulators must be given the tools and budgets to test inspect and trace; manufacturers must be held to transparent standards; and international partners must help strengthen laboratory networks and surveillance especially in countries with constrained resources.

Families who lost children in Madhya Pradesh deserve more than an apology; they deserve transparency about what went wrong and concrete steps that prevent future tragedies

References:

Reuters (2025). “Indian police arrest owner of cough syrup company linked to deaths of 19 children” Oct 9 2025; Reuters (2025). “India declares three cough syrups toxic after child deaths” Oct 9 2025.

Bonvoisin, T., et al. (2020). “Suicide by pesticide poisoning in India: a review of pesticide regulations and their impact on suicide trends.” BMC Public Health 20(1): 251.

Pesticide self-poisoning is a common means of suicide in India. Banning highly hazardous pesticides from agricultural use has been successful in reducing total suicide numbers in several South Asian countries without affecting agricultural output. Here, we describe national and state-level regulation of highly hazardous pesticides and explore how they might relate to suicide rates across India.

Bureau, N. C. R. (2023). “Accidental deaths and suicides in India.”

Eddleston, M. and D. Gunnell (2020). “Preventing suicide through pesticide regulation.” The Lancet Psychiatry 7(1): 9-11.

McMartin, K., et al. (2016). “Antidotes for poisoning by alcohols that form toxic metabolites.” British journal of clinical pharmacology 81(3): 505-515.

Perazella, M. A. (2023). “Hiding in Plain Sight: Catastrophic Diethylene Glycol Poisoning in Children.” Kidney360 4(11): 1534-1535.

Rollins, Y., et al. (2002). “Fulminant ascending paralysis as a delayed sequela of diethylene glycol (Sterno) ingestion.” Neurology 59(9): 1460-1463.

Schep, L. J., et al. (2009). “Diethylene glycol poisoning.” Clinical toxicology 47(6): 525-535.

World Health Organization (2023). Medical Product Alert N°8/2023: Substandard (contaminated) syrup and suspension medicines Dec 7 2023.

CDC (2009). MMWR report on diethylene glycol poisoning clusters in Nigeria 2009.

Chemistry World (2023). Coverage of the 2022–23 multi‑country contaminated syrup wave.

FDA (1938). Historical report on the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster and the 1938 Food Drug and Cosmetic Act.

Appendix 1

Source: National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of home, ministry of Home affairs, GoI

[1] The Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention is funded by the Good Ventures Foundation at the recommendation of Coefficient Giving.

[2] National Crime Records Bureau, 2023. Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India Year Wise

About the author:

Mounika Bhukya is currently pursuing her PhD education in Global Health Policy at the University of Edinburgh. Her research focusses on the commercial determinants of health in the pesticide industry in India. Mounika is a GRACT (Global Research Academy for Clinical Toxicology) Scholar and her PhD is partly funded by NIHR and University of Edinburgh. She has been working as a Project and Policy Officer with CPSP since 2022 on various research projects in India.

She also has experience in government partnerships and project implementation and has worked on various macro level policies in Health, Agriculture and Education sectors with the State and Central Government of India. She has previously worked with global organisations like UN Habitat, JPAL, IIHS and Indo-German Centre for Sustainability.

Mounika is passionate about cross-cultural problem solving, grassroots solutions, and is attempting to bridge policy gaps one intervention at a time.